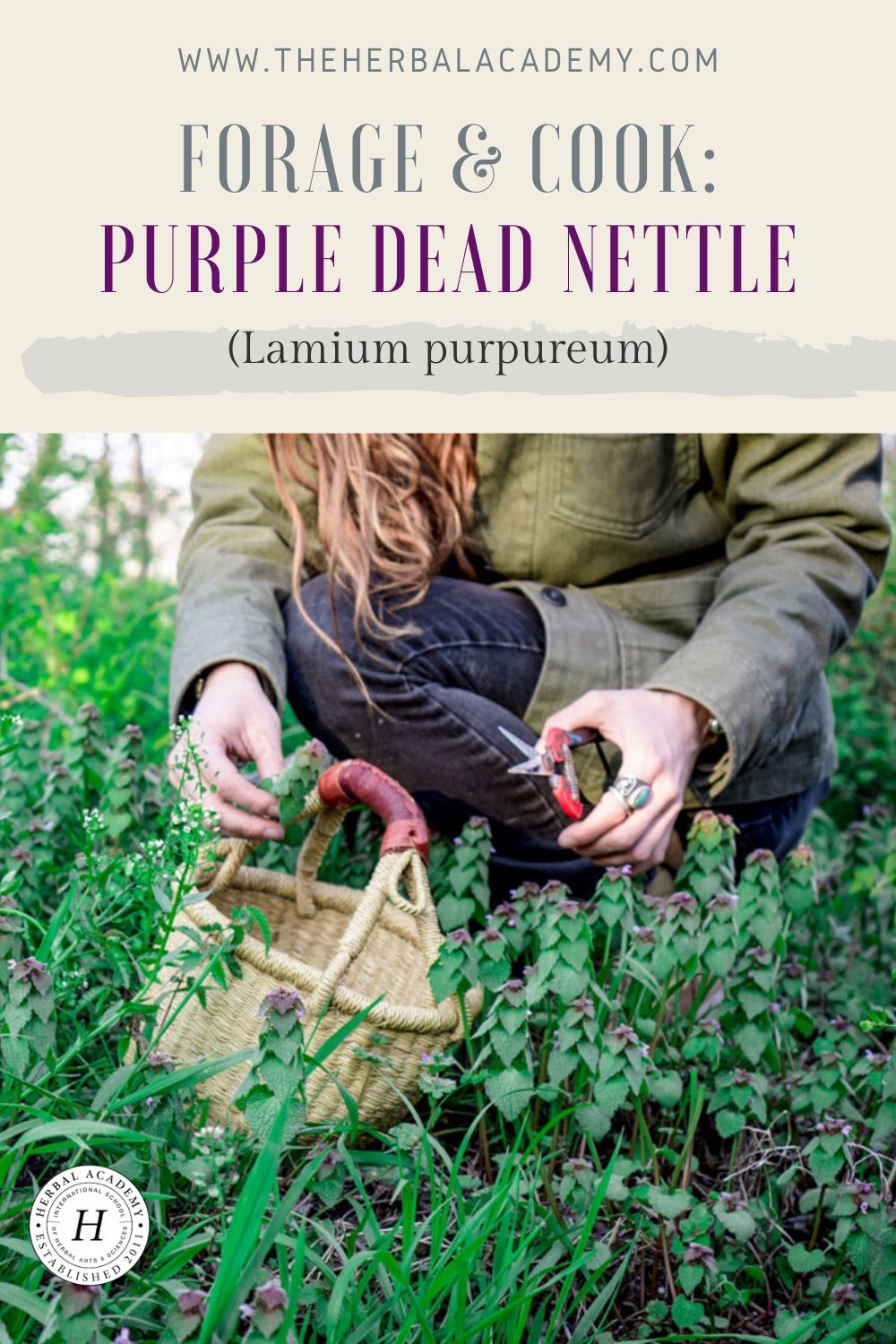

If you enjoy foraging and using plants that grow naturally around you, then purple dead nettle ( Lamium purpureum ) is a wonderful plant to become acquainted with. Available across most of the United States, this common “weed” is easy to find and its mild flavor blends well with a wide variety of recipes—from salads and smoothies to stir-fries and soups.

One of the characteristics that sets wild edibles apart from cultivated foods is their nutrient density; they tend to contain more beneficial nutrients like vitamins and minerals on a per-weight basis than cultivated foods (Milburn, 2004). This is attributed to a variety of causes. First, cultivated foods like vegetables have been selected for many generations for their size and hardiness rather than their nutritional value.

All cultivated foods originated as wild plants, and over the long history of agriculture, which was likely developed around 12,000 years ago (Uekoetter, 2010), humans have saved seeds and hybridized plants to genetically select larger, easy-to-grow varieties. Such plants make for greater crop yields, but tend to contain fewer nutrients than their wild counterparts (Davis et al., 2004).

WE RECOMMEND THE VIDEO: How To Distribute Pharma Business In Market,Pharma Marketing Tips

नोट-इस वीडियो में फार्मा डिस्ट्रीब्यूटर को फार्म फ्रेंचाइजी समझा जाये।। Pharma Marketing Tips How to Grow Pharma Business ...

This fascinating history provides us with all the more reason to enjoy a heaping plate of wild spring greens!

Dead nettle – Lamium purpureum (Lamiaceae) – Aerial parts

Known variously as red or purple dead nettle and purple archangel, L. purpureum is native to Europe, North Africa, and Siberia. It has naturalized in much of the United States, as well as Canada, Greenland, and Iceland (Royal Botanic Gardens of Kew, n.d.b.). White dead nettle ( L. album ), native throughout Europe and Asia (RBGK, n.d.a.), is the most commonly referenced Lamium species in herbal literature, although the two species have traditionally been used similarly (Grieve, 1931/1971). Dead nettle can be found in lawns and disturbed soils and is a common garden weed (Deer, 2016).

Botanical description: Like almost all members of the Lamiaceae (mint) family, dead nettle has square stems and opposite leaves. Dead nettle grows up to 45 cm tall (Steckel, n.d.), and has dark green to purplish ovate leaves with crenate margins (margins with rounded teeth) (New York Botanical Garden, n.d.). Leaves grow up to 2½ cm long (Steckel, n.d.); on the lower part of each stem the leaves are spaced widely apart, but they grow quite close together at the top of the stem, near the flower whorls. Each flower whorl has 6-10 pink or purple flowers, which technically have five petals, but these petals are fused together into a two-lipped tube approximately 5 mm long (Magee & Ahles, 1999).

Actions: Antihistamine, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, astringent, immunostimulating, nutritive, styptic

Energetics: Warming and drying

Use: One of the earliest spring greens available in the season, dead nettle is named for its leaves, which are similar in shape to stinging nettle ( Urtica spp.), but are “dead” due to their lack of sting (Grieve, 1931/1971). The flowering tops can be finely chopped for inclusion in salads, smoothies, or cooked dishes like soups, sauces, egg dishes, and stir-fries. Dead nettle’s somewhat fluffy texture lends itself especially well to fritters (see recipe below!). The plant has an earthy odor that may be disagreeable to some but is dissipated upon cooking; the taste is fairly mild with slightly bitter undertones.

Purple dead nettle contains polyphenols—compounds with antioxidant properties (Vergun et al., 2019) that are associated with a broad range of health benefits, especially for the cardiovascular system (Fraga et al., 2010) and the gut microbiome (Cardona et al., 2013). It is also a source of quercetin, a flavonoid with immunostimulating and anti-inflammatory properties that is used to ease allergies and other chronic inflammatory issues like rheumatism (Deer, 2016). The plant’s volatile oil content has antimicrobial properties and may be helpful against candida overgrowth (Deer, 2016). Its astringent properties have traditionally been used to staunch bleeding (Grieve, 1931/1971), including excessive menstrual bleeding (Wood, 2008).

Harvesting and processing: Harvest the first 5-10 cm of the flowering tops in the early spring. Dead nettle is often confused with henbit ( Lamium amplexicaule ), another member of the Lamiaceae (mint) family that is low-growing with purple flowers; however, henbit is also edible!

Safety: There are no known contraindications, but those with excessive uterine bleeding should seek a physician’s care to rule out malignancy before using Lamium species as a hemostatic (Aleschewski, 2008).

Cooking with Dead Nettle

Knowing that dead nettle contains antioxidant, immunostimulating, and anti-inflammatory properties has us all the more excited to hit the fields, find an abundant patch, and then experiment with this lovely spring green in our kitchens!

The following recipes are from The Foraging Course , an in-depth, seasonal guide into the plants that grow around you and how to use them.

Dead Nettle and Chickweed Fritters

This savory fritter recipe makes use of the fluffy texture of dead nettle combined with chickweed, another early spring plant that can often be found growing nearby. These dark-green delights are surprisingly filling and make a great breakfast fritter, or they can be served as a side dish for other meals.

2 tbsp coconut oil

5 cups (2 oz) dead nettle ( Lamium purpureum ) flowering tops, finely chopped

2 cloves garlic, minced

3 cups (1.5 oz) chickweed (Stellaria media) aboveground parts, finely chopped

1 egg, whisked

- In a medium-sized skillet, melt 1 tablespoon of the coconut oil on medium-low heat.

- Add dead nettle and garlic and sauté about 10 minutes until garlic browns slightly.

- Add chickweed and sauté until tender, about 2 minutes.

- Remove from heat and transfer sautéed vegetables into a heat-safe bowl.

- Add egg and thoroughly mix until combined.

- Return skillet to heat; add 1 tablespoon coconut oil and transfer vegetable mixture back into skillet.

- Form into 4 fritters (about 2-3 inches in diameter).

- Flatten fritters with a spatula and cook 1-2 minutes on each side, flipping as necessary, until the outside turns brown and crispy.

Dead Nettle and Mint with Smoked Garlic

Adapted from Hunter Gather Cook (Hunter Gather Cook, 2012).

This simple side dish combines the mild flavor of dead nettle with zingy wild mint.

1 tbsp butter or olive oil

1 smoked garlic clove, finely chopped or grated

3 oz dead nettle ( Lamium purpureum ) flowering tops

15 wild mint ( Mentha spp.) leaves

½ lime, juiced

Salt and pepper to taste

Dead nettle flowers, for garnish (optional)

- Heat butter or olive oil in a skillet over low heat.

- Add garlic and sauté for 1-3 minutes.

- Add dead nettle and mint and sauté for approximately 5 minutes.

- Season with lime juice, salt, pepper.

- Garnish with fresh dead nettle flowers, if desired.

Join us in The Foraging Course to learn all about harvesting and using wild plants—from springtime beauties, such as nettle, violet, and chickweed to summertime treasures, like yarrow, mimosa, and mugwort—not to mention our fall favorites like burdock, yellow dock, and rosehip. With this in-depth, online guide, you will learn how to safely identify and harvest wild plants. You’ll also receive 24 in-depth plant monographs about common wild botanicals and 48 tested recipes for using your harvest both in your kitchen and in your apothecary.

Aleschewski, N. (Ed). (2008). Lamium album [Southern Cross University website]. Retrieved from https://www.scu.edu.au/southern-cross-plant-science/facilities/medicinal-plant-garden/monographs/lamium-album/

Cardona, F., Andrés-Lacueva, C., Tulipani, S., Tinahones, F., & Queipo-Orutño, M.I. (2013). Benefits of polyphenols on gut microbiota and implications in human health. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry , 24 (8), 1415-1422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnutbio.2013.05.001

Davis, D., Epp, M., & Riordan, H. (2004). Changes in USDA food composition data for 43 garden plants, 1950-1999. Journal of the American College of Nutrition , 23 (6), 669-682. https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2004.10719409

Deer, T.S. (2016). Allergy sufferers get ahead with purple dead-nettle. Retrieved from https://wisdomoftheplantdevas.com/tag/medicinal-plants-2/

Fraga, C.G., Galleano, M., Verstraeten, S.V., & Oteiza, P.I. (2010). Basic biochemical mechanisms behind the health benefits of polyphenols. Molecular Aspects of Medicine, 31 (6), 435-445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mam.2010.09.006

Grieve, M. (1971). A modern herbal (Vols. 1-2). New York, NY: Dover Publications. (Original work published 1931)

Hunter Gather Cook. (2012). Red dead-nettle: A spring side dish. Retrieved from https://huntergathercook.typepad.com/huntergathering_wild_fres/2012/04/red-dead-nettle-a-spring-side-dish.html

Magee, D.W., & Ahles, H.E. (1999). Flora of the Northeast . Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press.

Milburn, M. (2004). Indigenous nutrition: Using traditional food knowledge to solve contemporary health problems. American Indian Quarterly , 28 (3-4), 411-434. https://doi.org/10.1353/aiq.2004.0104

New York Botanical Garden. (n.d.). New York City EcoFlora: Lamium . Retrieved from https://www.nybg.org/content/uploads/2018/03/NYBGEcoQuest_2018_March_LookForLamium_MoreInformation.pdf

Royal Botanic Gardens of Kew. (n.d.a). Lamium album L. Plants of the world online [Database]. Retrieved from http://www.plantsoftheworldonline.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:448792-1

Royal Botanic Gardens of Kew. (n.d.b). Lamium purpureum L. Plants of the world online [Database]. Retrieved from http://www.plantsoftheworldonline.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:448939-1

Steckel, L. (n.d.). Purple dead nettle and henbit. University of Tennessee Extension. Retrieved from https://extension.tennessee.edu/publications/Documents/W165.pdf

Uekoetter, F. (Ed.) (2010). The turning points of environmental history . Pittsburgh, PA: University of PIttsburgh Press.

Vergun, O.M., Grygorieva, O.V., Brindza, J., Shymanska, O.V., Rakhmetov, D.B., Horčinová-Sedlačková, V., … Ivanišová, E. (2019). Content of phenolic compounds in plant raw of Cichorium intubus L., Lamium purpureum L. and Viscum album L. Plant Introduction , 84, 87-96. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3404149

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to email this to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

A Free Ebook Just For You!

Sign up for the Herbal Academy Newsletter, and we'll send you a free ebook.

Please add your email address below and click "Submit" to add yourself to our mailing list. Then check your email to find a welcome message from our Herbal Academy team with a special link to download our " Herbal Tea Throughout The Seasons " Ebook!

You have Successfully Subscribed!

About Post Author

Herbal Academy

Related Articles

Disclosure

The Herbal Academy supports trusted organizations with the use of affiliate links. Affiliate links are shared throughout the website and the Herbal Academy may receive compensation if you make a purchase with these links.

Information offered on Herbal Academy websites is for educational purposes only. The Herbal Academy makes neither medical claim, nor intends to diagnose or treat medical conditions. Links to external sites are for informational purposes only. The Herbal Academy neither endorses them nor is in any way responsible for their content. Readers must do their own research concerning the safety and usage of any herbs or supplements.